Static Stretching vs

Active Isolated Stretching

The Gold Standard? Maybe not...

For years static stretching has been considered the gold standard of stretching techniques.

Barely a week goes by without a client coming into my office and telling me they’ve diligently tried to stretch out their lower back or their hamstrings but haven’t made any progress.

They show me the stretches they’ve been doing and, 9 times out of 10, I’m presented with a series of stretches of the static variety.

What are they doing wrong? they ask. What’s the problem?

The problem is that, especially with very tight muscles, this type of stretch is not very effective, and sometimes can even create greater strain in the body.

What is Static Stretching?

A static approach to stretching is simply a stretch in which a muscle is put into a elongated state for 30 seconds or more and held there without movement. Some advocates of this technique suggest holding the stretch up to 2 minutes.

The goal, of course, is to try to improve the resting length of the muscle.

The Protective Stretch Reflex

The problem with this type of stretching is that it often provokes what’s called the protective stretch reflex. You’ve probably felt this reflex many times. Tell me if this sounds familiar…

Determined to stretch yourself out, you put a muscle on a strong static stretch and then you hold it there with a grim determination.

But instead of the muscle lengthening, it fights back at you, quivering and resisting. Sometimes you feel worse than when you started.

If this has happened to you, you’re not alone.

The protective stretch reflex is a natural response in our muscles designed to prevent them from being injured. Static stretching often triggers this reflex and it is particularly strong in muscles that are very tight and short.

This reflex not only often inhibits muscle lengthening but can reduce muscle responsiveness. For athletes, recent studies suggest that static stretches can decrease performance by creating fatigue in muscles.

With respect to lower back pain, these static holds can aggravate the body leading to more pain, not less.

When is Static Stretching Appropriate?

Because of the protective stretch reflex, I don't recommend this type of stretching in cases where muscles are extremely tight and short.

However, once muscles have achieved a certain degree of flexibility (using techniques such as Active Isolated Stretching, described below), then it's possible to help maintain the achieved length using a both static and weight bearing stretching techniques.

The most common type of static and weight-bearing stretching my clients ask about is yoga.

Yoga poses such as the Warrior One...

Or the Extended Triangle Pose...

...are both examples of static, weight-bearing stretches.

Yoga, of course, is a much more dynamic activity than a basic stretching technique and too often yoga is viewed simply as a strategy to improve flexibility.

The problem with this is that individuals end up straining themselves in a attempt to do things their bodies are not ready for.

A Powerful Alternative: Active Isolated Stretching

A much better strategy to lengthen tight, short muscles is a method called Active Isolated Stretching.

This technique was developed by Kinesiotherapist Aaron Mattes who I met and worked with for the first time at a seminar in Costa Rica a number of years ago.

Aaron has developed this technique over the past forty years and, since incorporating Active Isolated Stretching into my Neuromuscular Therapy practice, I have found it to be the most effective stretching technique I’ve ever used, especially for clients with very tight, short, hard-to-stretch muscles.

How Active Isolated Stretching Works

Active Isolated Stretching is effective because it does not provoke the protective stretch reflex and therefore allows for actual, progressive lengthening of muscle fibers.

This stretching technique accomplishes this feat by using a repeated 2-second stretch (repeated 10-12 times) rather than holding a static stretch. This allows the muscle to lengthen progressively.

Three basic steps are used in Active Isolated Stretching…

Here we’ll use the hamstrings as an example since the hamstrings are notoriously tight in many of us and are also a major contributor to lower back pain:

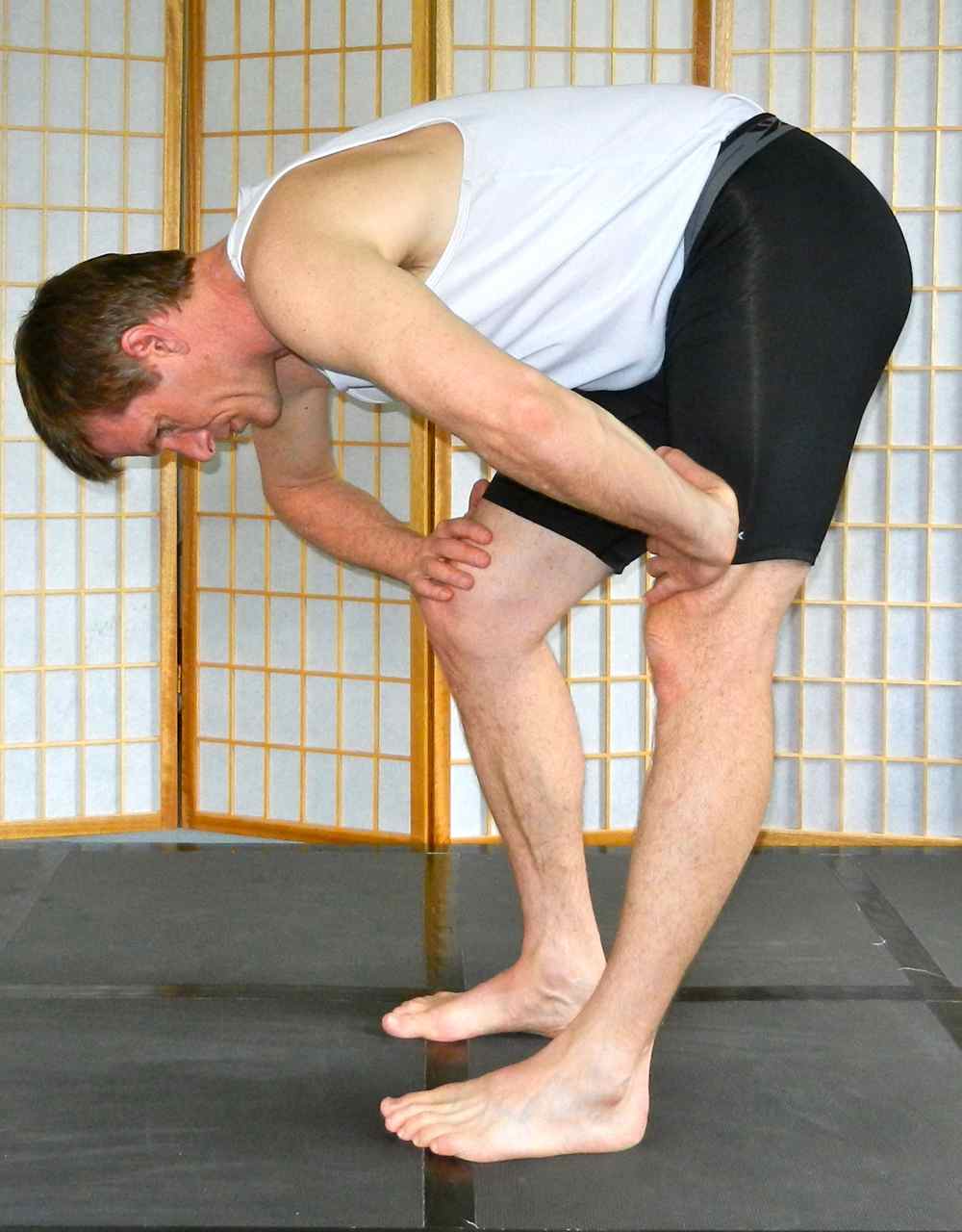

Step 1. Make sure the muscle is not bearing weight

If

a muscle is bearing weight as is often done, for example, with standing

hamstring stretches, the hamstrings are eccentrically contracted, not

an optimal state for attempting to create length in a muscle.

Step 2. Activate of the antagonist of the muscle being stretched

By

activating the antagonist of the muscle being stretched, this technique

takes advantage of what’s called reciprocal inhibition, a neuromuscular

reflex which prevents muscles on both sides of joint from contracting

at the same time. In the video on the hamstring stretches page you can

see that as the quadriceps contract, the hamstrings must relax.

Step 3. Hold the stretch for no more than 2 seconds

By

holding the stretch for only 2 seconds the protective stretch reflex is

not triggered, thus enabling a progressive lengthening of the muscle.

For examples of how to perform Active Isolated Stretching please see the Stretching Videos Page

Return to Top | Causes Index | Home Page

Anatomy Images Courtesy of BIODIGITAL

Stephen O'Dwyer, cnmt

Neuromuscular Therapist & Pain Relief Researcher

FOUNDERLower Back Pain Answers |

|

CURRENT COURSES POSTURAL BLUEPRINT FOR CORRECTING PELVIC TORSION: The Complete Guide To Restoring Pelvic Balance (2022) STRETCHING BLUEPRINT FOR PAIN RELIEF & BETTER FLEXIBILITY: The Complete Guide to Pain-Free Muscles Using Active Isolated Stretching (2020) HEALING THE HIDDEN ROOT OF PAIN: Self-Treatment for Iliopsoas Syndrome (2013) FREE MINI COURSE: Introduction to Active Isolated Stretching |