The Essentials of Diaphragmatic Breathing

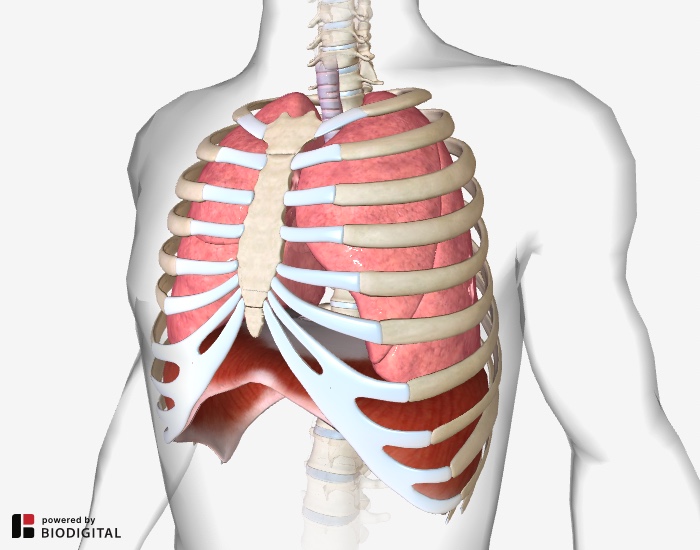

Diaphragmatic breathing is accomplished by proper use of the diaphragm muscle. This is a large, dome-shaped muscle located at the base of the lungs. This muscle functions to pull air into the lungs and then to expel it.

Imagine an umbrella inverting with your in-breath and then with the out-breath, returning to its umbrella shape. Your abdominal muscles assist in the action of emptying the lungs by contracting as you breathe out.

If the diaphragm muscle is not used fully, as occurs with shallow breathing, it can become atrophied or chronically tight. This, then, leads to chronic shallow breathing in which an individual always feels “out of breath” or “gets winded” easily.

Shallow or Paradoxical Breathing

Shallow breathers are also known as chest breathers or paradoxical

breathers. They are called chest breathers due to the fact that only the

chest expands and contracts during breathing. For many of us this is a

common sight:

An individual taking a big breath sucks in their belly while their chest inflates.

You may ask... What’s wrong with that? Doesn’t this action fill my lungs with the maximum amount of breath?

The answer is no.

This

type of breathing is actually quite shallow because the diaphragm

muscle is not permitted to expand downward. Why? Because the contracting

abdominals are in moving inward, taking up space. To summarize, shallow

breathing is also known as paradoxical breathing because of two opposing forces are attempting to occupy the same space:

- The diaphragm is attempting to expand downward into the abdominal cavity while...

- The abdominal muscles are contracting inward, occupying the same space.

You can’t do both. Therefore, paradoxical breathing can lead to a number of problems.

Problems Caused by Paradoxical Breathing

There are numerous problems caused when paradoxical breathing substitutes for diaphragmatic breathing. The lack of movement in the diaphragm can cause:

- Intra-abdominal pressure, interfering with digestion, elimination, or the menstrual cycle

- Chronic tightening of muscles in the chest and neck which are meant to assist in respiration, but not meant to take over the action of the diaphragm. These muscles include: scalenes (in the neck), pectoralis major and minor (in the chest), serratus anterior (wraps around the ribcage on the underside of the arms), serratus posterior superior and inferior (in the back).

- Chronic tightening of the core muscles of the body, including the muscles of the lower back

The Diaphragm and Lower Back Pain

Disuse of the diaphragm due to shallow breathing can lead to

tightening of the muscular core of the body, including the back muscles.

The tightening and shortening of the back muscles, especially the back extensors, shifts the position of the ribcage so that the diaphragm cannot move freely. If the diaphragm cannot fully expand and contract, the back muscles have a difficult time relaxing.

Instead of the ribs expanding and contracting with each breath, the ribcage moves up and down as a static unit.

Learning to Breathe Diaphragmatically

When you first learn to breathe diaphragmatically, it may be easier to practice while lying down. As you gain more experience, you can try the diaphragmatic breathing technique while sitting in a chair as well.

At first, breathing diaphragmatically may feel awkward or like you have to use a lot of effort. This is normal. If you haven’t exercised a muscle in a while, that muscle will be uncoordinated and unfamiliar with the action you’re asking of it.

However, with continued practice diaphragmatic breathing becomes much easier, and much more comfortable. In fact, once you’re a diaphragmatic breather, it may feel wrong to breathe any other way!

Diaphragmatic Breathing Technique

1. Lie on your back on a flat surface or in bed, or sit comfortably in a chair.

2.

Place one hand on your upper chest and the other hand just below your

ribcage on your belly. This will allow you to feel the movement of your

diaphragm as you breathe.

3. Breathe in slowly through your

nose so that your belly moves out against your hand. The hand on your

chest should remain as still as possible.

4. When you breathe

out, gently contract your abdominal muscles, letting them fall inward

as you exhale through pursed lips. The hand on your upper chest must

remain as still as possible.

5. As you begin to have

control over the movement of the belly, and the stillness of the chest,

you can then begin to coordinate their expansion...

6. Now when you breathe in and out, allow both hands to rise and fall simultaneously. This action permits the fullest expansion of the diaphragm.

Anatomy Images Courtesy of BIODIGITAL

Stephen O'Dwyer, cnmt

Neuromuscular Therapist & Pain Relief Researcher

FOUNDERLower Back Pain Answers |

|

CURRENT COURSES POSTURAL BLUEPRINT FOR CORRECTING PELVIC TORSION: The Complete Guide To Restoring Pelvic Balance (2022) STRETCHING BLUEPRINT FOR PAIN RELIEF & BETTER FLEXIBILITY: The Complete Guide to Pain-Free Muscles Using Active Isolated Stretching (2020) HEALING THE HIDDEN ROOT OF PAIN: Self-Treatment for Iliopsoas Syndrome (2013) FREE MINI COURSE: Introduction to Active Isolated Stretching |