True Sciatica

what it is and how to relieve it

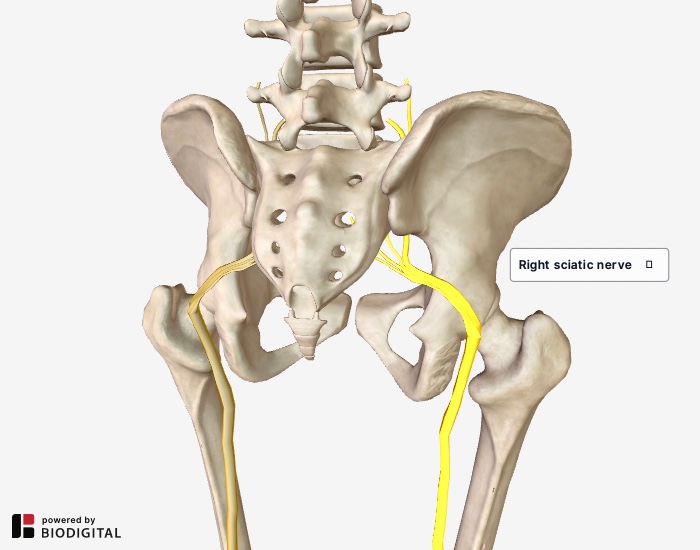

Right sciatic nerve highlighted.

Right sciatic nerve highlighted.True sciatica is caused by pressure on the sciatic nerve at the nerve root. The most common cause of pressure is a bulging or herniated disc which compresses the nerve near the spine. It is a form of nerve compression not to be confused with nerve entrapment, such as in the case of Piriformis Syndrome.

Nerve compression of this type might cause pain, aching, burning, tingling, numbness, or weakness anywhere along the path of the sciatic nerve which runs from the lumbar spine through the buttocks, down the back of the thigh, then divides into two branches in the lower leg.

Sensations may radiate anywhere along the nerve, from the lower back as far down as the foot. These sensations might be worse when sitting, or when moving from sitting to standing, but can also be relatively constant. Walking might also aggravate the discomfort.

More rarely, sciatica is caused by abnormalities in the lumbar vertebrae itself, like a narrowing of the spinal cavity called spinal stenosis. Trauma or disease might also account for pressure on the sciatic nerve.

X-rays and MRIs are commonly administered to determine if there’s a bulging disc putting pressure on the sciatic nerve. Unfortunately the presence of a bulging or deteriorated disc is not proof positive that such pressure exists.

Often by the age of twenty years old, much of the population has some deterioration in the discs of the lower back and not all have pain.

Sciatica is Often Misdiagnosed

When there is pain in the lower back, the buttocks or down the back of the leg, sometimes traveling as far as the foot, “sciatica” is often the first condition named.

Certainly there is some logic to this since the sciatic nerve (the largest nerve in the body) travels from the lower back through the buttocks and down the back of the leg.

But in a high percentage of cases pain felt in the buttocks and down the back of the leg is not caused by sciatica but by chronically tight muscles and by referred sensations from active myofascial trigger points.

Muscles in the lower back and buttocks can become chronically tight and painful for a variety of reasons including inactivity, stress, and structural imbalance in the pelvis which can set up a pattern of muscular compensation.

Muscles become painful when they are

ischemic, meaning when they have inadequate blood flowing to them. You

can readily see an example of this when you make a fist and your

knuckles go white.

This is what happens to a muscle that is chronically contracted. Without adequate blood flow to a muscle, there’s a perpetual build up of lactic acid and no way for that acid to clear out making room for oxygen and nutrients.

This ischemic state, a state of inadequate blood flow to the muscles, creates a perfect environment for trigger points to become active. A trigger point is an area in an ischemic muscle that refers sensation to another part of the body.

Please note that the referred sensation of a trigger point is not the same thing as the referred sensation from a compressed nerve. The distinction is important in order to provide the most targeted treatment possible.

Symptoms that look like Sciatica but Aren't

Here’s an example of a common scenario that, at first glance, seems like it might be sciatica but, in fact, is not:

A client comes into my office with pain in the right buttocks that sometimes shoots down the back of his leg. When I evaluate his structure we find that there’s a torque in his pelvis causing his right leg to be functionally long. It is very common for the gluteal muscles on the side of the functionally long leg to get overworked.

Upon inspecting the right buttocks muscles (gluteals) I find them to be extremely tight. Further, when I apply direct pressure to them, I am able to reproduce the sensation my client typically experiences down his leg. That tells me we’ve identified active trigger points in his gluteal muscles.

To be sure, I also perform two standard sciatica leg raise tests to see if it reproduces his symptoms. When it does not, we are able to conclude a familiar pattern:

1) Structural imbalance in my client’s pelvis has caused a functional leg length difference and led to overuse, and thus chronic contraction of, the right gluteal muscles.

2) Chronic contraction of the right gluteal muscles has caused them to become ischemic (low blood flow) causing a build up of lactic acid. This leads to the activation of trigger points in those muscles.

3) Trigger points in the gluteals are causing the referred sensation down the leg, not sciatica.

In this scenario, the appropriate treatment protocol will be a two-pronged approach:

1) Correct the structural imbalance causing the right gluteal muscles to chronically contract, then...

2) Directly treat the painful gluteal muscles with detailed massage and myofascial treatment as needed.

Why Are These Distinctions Important?

It’s important to make the distinction between true sciatica and pain that’s mimicking sciatica because otherwise we miss the most frequent cause of pain: the muscles.

Muscles receive little attention in modern medical school teaching and medical textbooks. Consequently, physicians give a disproportionate amount of attention to nerves, joints, bursae, and bones at the expense of the largest organ in the body: skeletal muscle.

Inattention to what’s happening in the musculoskeletal system often results in medical confusion with respect to lower back pain and other chronic pain.

The common decree, “You have sciatica… get some physical therapy,” is often neither an accurate diagnosis, nor a sound therapeutic prescription.

While physical therapy is tremendously effective for many types of treatment such as rehabilitation of an atrophied limb after a cast has come off or stabilizing a weak joint with strengthening exercises, it does not tend to deal effectively with chronic pain, much less with correcting structural imbalance.

Further, you cannot plug an individual into a generic program of back strengthening exercises. Strengthening is NOT the first thing that needs to happen when someone is in pain, and can often be detrimental to recovery if introduced too soon.

The correct order for rehabilitation is:

1) Relieve the spasms and hyper-constriction in the affected muscles

2) Restore proper biomechanics to the body

3) Restore flexibility to the tissues

4) Rebuild strength of the injured tissues

5) Rebuild endurance

What if I Do Have Sciatica?

True sciatica can be determined by a standard leg-raise test and confirmed by ruling out trigger point referrals:

1) A standard leg raise test is done with the patient supine, the symptomatic leg is raised, and the foot dorsiflexed.

If pain is felt in the symptomatic regions, there is presumptive evidence of sciatica.

2) To confirm that trigger points are not also contributing to the problem, all the muscles that can possibly refer sensation (via trigger points) into the buttocks and down the leg (gluteals, quadratus lumborum, hip rotators, hamstrings, etc.) must be palpated.

If no trigger points are identified by referred sensations, then it is reasonable to believe the sciatic nerve is being compressed by a nerve or entrapped by soft tissue.

If sciatic nerve compression is the diagnosis, it’s essential to create the best environment possible for the discs and related nerve structures. To do that, proper structural alignment is essential.

If a disc is compressing the sciatic nerve, it’s crucial to improve alignment to remove that compression. If the sciatic nerve is being entrapped by peripheral soft tissues such as muscle or fascia, it essential to release those muscles and lengthen that fascia to relieve that entrapment.

Can I Achieve Proper Structural Alignment by Going to a Chiropractor or Osteopath?

Both chiropractic and osteopathic manipulation can be very useful in helping to achieve proper structural alignment, but both are greatly enhanced in their efficacy by thorough soft tissue work done first.

Here I don’t mean just a quick fifteen minute massage before the adjustment, though that’s certainly preferable to no soft tissue warm-up at all.

Rather I mean very detailed muscular and fascial release work which will not only prepare the body so that much less force is needed for the adjustment, but will make the adjustment last much longer.

Return to Top | Causes Index | Home Page

Anatomy Images Courtesy of BIODIGITAL

|

CURRENT COURSES POSTURAL BLUEPRINT FOR CORRECTING PELVIC TORSION: The Complete Guide To Restoring Pelvic Balance (2022) STRETCHING BLUEPRINT FOR PAIN RELIEF & BETTER FLEXIBILITY: The Complete Guide to Pain-Free Muscles Using Active Isolated Stretching (2020) HEALING THE HIDDEN ROOT OF PAIN: Self-Treatment for Iliopsoas Syndrome (2013) FREE MINI COURSE: Introduction to Active Isolated Stretching |