Myofascial Trigger Points

THE ROOT OF REFERRED Lower Back & Hip Pain

Myofascial trigger points are one of the most prevalent causes of pain in the body and yet this phenomenon is not well understood in conventional medicine.

The chief reason for this shortcoming is that medical schools still devote very little attention to the muscular system, and trigger points are a muscular phenomenon.

But if you are suffering from pain that has eluded diagnosis, it's essential to clearly understand how myofascial trigger points work.

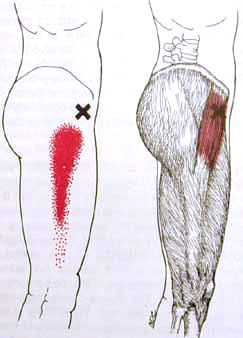

Myofascial Trigger Point in the Tensor Fascia Lata referring down the thigh.

Myofascial Trigger Point in the Tensor Fascia Lata referring down the thigh.Definition

We owe our understanding about myofascial trigger points to the groundbreaking two-volume work, Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, by Dr. Janet Travell & Dr. David Simons.

Drs. Travell and Simons define a trigger point as follows…

|

A hyperirritable spot, usually within a taut band of skeletal muscle or in the muscle’s fascia, that is painful on compression and that can give rise to characteristic referred pain. |

The key part of this definition is the last phrase:

“…can give rise to characteristic referred pain.”

What distinguishes myofascial trigger points from other tender points is that it creates a referred sensation — pain, tingling, numbness, aching, or thermal sensations like hot or cold.

This referred sensation can either radiate out from the point, or it can refer to another part of the body.

If a point is simply tender but does not refer, we call it an ischemic point (a region of poor blood flow).

Too often health professionals toss around the term “trigger point” to refer to any tender point in the body.

But this just creates confusion in identifying true trigger points.

Nerve Root Referral vs Trigger Point Referral

A trigger point referral IS NOT caused by compression, “pinching,” or pressure on a nerve of any kind.

That describes a nerve root referral in which pain is caused due to the compression or entrapment of a nerve by bone, cartilage, or soft tissues.

Two examples of a nerve root referral can be illustrated with the sciatic nerve which travels from the lumbar spine through the buttocks and down the leg. The sciatic nerve can be…

- Compressed by a bulging or herniated spinal disc resulting in nerve root compression

- Entrapped by the piriformis muscle resulting in muscle entrapment

In both cases, pressure on one part of the nerve sends sensation — pain, tingling, or numbness — to another part of the nerve. The region of sensation is called the referral zone.

A trigger point referral, on the other hand, is a muscle-based phenomenon.

When muscles become ischemic (low blood flow) as a consequence of strain or chronic contraction, a strange neurological phenomenon can occur…

The muscle can begin to send a signal to the central nervous system. Then from the central nervous system that signal can travel out to another part of the body causing sensation.

For example, if I have a trigger point in a muscle in my lower back it could send a signal to my central nervous system which would then send a signal to my buttocks and I would feel pain there.

The pain, then, would not be caused by a nerve being pinched or compressed in my lower back, but rather by the trigger point creating a feedback loop of signals: from my lower back to my nervous system to my buttocks.

What Causes Myofascial Trigger Points?

Myofascial trigger points can develop within skeletal muscles and fascia for a wide variety of reasons:

- Sudden trauma to musculoskeletal tissues (muscles, ligaments, tendons, bursae)

- Injury to intervertebral discs

- General fatigue (Fibromyalgia is a perpetuating factor for Trigger Points. Some evidence suggests Chronic Fatigue Syndrome may produce TPs as well)

- Repetitive motions; excessive exercise; muscle strain due to over activity

- Systemic conditions (eg, gall bladder inflammation, heart attack, appendicitis, stomach irritation)

- Lack of activity (eg, a broken arm in a sling)

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Hormonal changes (eg, TP development during PMS or menopause)

- Nervous tension or stress

- Chilling of areas of the body (eg, sitting under an air conditioning duct; sleeping in front of an air conditioner)

OTHER TYPES OF TRIGGER POINTS

In addition to primary myofascial trigger points, two other forms of these pain-referring points are also possible:

- Secondary

- Satellite

Both of these types can help us sort out an otherwise bewildering assortment of pain and symptoms in the body.

SECONDARY TRIGGER POINTS

A secondary trigger point can arise due to muscular compensation. For example, let’s say I sit a lot for my job and this results in a primary trigger point developing in my right iliopsoas muscle.

Because the iliopsoas muscle is the primary hip flexor used to raise my leg in walking, it may be painful to take a step with my right leg.

In order to be able to take a step with less pain, my body might make an adjustment when I take that step. One common adjustment is to externally rotate the leg slightly just prior lifting the leg.

This takes some stress off the iliopsoas and transfers it to the adductor muscles located in the inner thigh.

But the adductor muscles are not designed for this job and so can easily become overworked making them chronically tired and sore.

Repeated use of tired and sore muscles can cause a trigger point to develop in them. Thus, a myofascial trigger points could develop in one of the adductor muscles. That would be called a secondary trigger point.

It’s also worth noting that in this example all or most of my symptoms might reside in the inner thigh, in the adductor muscles.

While the main problem remains in the iliopsoas, the source of the primary trigger point, the loudest symptoms could be elsewhere.

SATELLITE TRIGGER POINTS

A satellite trigger point can arise when the referral zone of a primary trigger point has itself become ischemic.

For example, let’s say I have a job that causes me to be hunched over much of the day.

A hunched over physical posture in which the shoulders are continually rounded forward can exert strain on the infraspinatus muscle (the middle muscle of the shoulder’s rotator cuff).

Such continuous strain could cause the development of a primary myofascial trigger points in the infraspinatus. It is not uncommon for a trigger point in the infraspinatus to refer sensation to the front of the shoulder.

Should this issue go untreated for a period of time the front of the shoulder might itself become ischemic.

Then any of the muscles or tendons located at the front of the shoulder could develop its own trigger point. This, then, would be a satellite trigger point. A frequent satellite trigger point of the infraspinatus muscle is the tendons of biceps muscle.

In this example an individual might have chronically rounded shoulders, develop a trigger point in the infraspinatus, but not experience symptoms in that rotator cuff muscle.

All symptoms might be in the front of the shoulder compounded by...

- The referral sensation from the infraspinatus and also

- The new satellite trigger point in the biceps tendons.

METHODS TO TREAT and resolve myofascial TRIGGER POINTS

The good news about myofascial trigger points is that they are very treatable. Three effective treatment strategies include:

MANUAL (HANDS-ON) THERAPIES

Various types of massage and bodywork can be very effective in interrupting and eliminating trigger points. Compression, kneading, stroking, & myofascial release of muscles and their fascia are all effective methods.

In my private practice my preferred method is a technique called Neuromuscular Massage Technique. What distinguishes this type of hands-on therapy is the use of a single direction stroke and also determining the client’s direction of stroke preference.

This tells the therapist the most calming stroke direction for the muscle. The most calming stroke direction will achieve the fastest positive results.

Also see Trigger Point Massage Therapy.

MUSCLE lengthening using active isolated stretching

Stretching out muscles that contain myofascial trigger points can contribute significantly to the elimination if these points and their referral patterns.

However, if a trigger point has been active for a significant period of time the muscle may require manual therapy before stretching is effective.

The reason for this is that a muscle containing an active trigger point can neither fully lengthen nor fully contract. This is also why you cannot properly strengthen muscles with trigger points.

Also I have found that Active Isolated Stretching is vastly superior to static stretching, especially in cases of very tight, very stubborn muscles.

activation and toning of the antagonists of trigger points

Among the most overlooked strategies for treating chronic muscular tightness in general and trigger points in particular is the activation of antagonists.

Muscles which are chronically tight and short, especially those with active trigger points, will often have very weak antagonists. Sometimes the antagonist muscles are not firing at all.

The reason for this is a phenomenon called reciprocal inhibition, also known as reciprocal innervation.

When a muscle on one side of a joint contracts and shortens, the muscle on the other side of the joint is neurologically signaled to relax and lengthen.

Without this phenomenon we could not have coordinated movement in the body. When your elbow bends, the biceps contract while the triceps lengthen. The triceps, here, is reciprocally inhibited.

In cases where a muscle has become chronic contracted, it's antagonist can become atrophied thus disrupting the reciprocal relationship between agonist and antagonist.

By toning the antagonist of a chronically contracted muscle we can, in effect, deactivate the chronic contraction, thus also deactivating the trigger point in that muscle.

ICE MASSAGE

Just as cold reduces inflammation in muscles, cold can also alleviate trigger points. A technique described in Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual is the use of something called vapocoolant spray.

But more recently ice has replaced such sprays. A simple ice method is to place a tongue depressor in a cup of water then freeze it. This creates a kind of ice popsicle that can then be used to stroke the muscle containing the active trigger point.

Stroking the muscle with 3-5 sweeps in one direction is typically adequate.

Return to Top | Causes Index | Home Page

Anatomy Images Courtesy of BIODIGITAL

Stephen O'Dwyer, cnmt

Neuromuscular Therapist & Pain Relief Researcher

FOUNDERLower Back Pain Answers |

|

CURRENT COURSES POSTURAL BLUEPRINT FOR CORRECTING PELVIC TORSION: The Complete Guide To Restoring Pelvic Balance (2022) STRETCHING BLUEPRINT FOR PAIN RELIEF & BETTER FLEXIBILITY: The Complete Guide to Pain-Free Muscles Using Active Isolated Stretching (2020) HEALING THE HIDDEN ROOT OF PAIN: Self-Treatment for Iliopsoas Syndrome (2013) FREE MINI COURSE: Introduction to Active Isolated Stretching |